Practical Tips for Writing Effective IEPs

One of the most crucial tools in a student’s school experience is their individulized education program (IEP). An effective IEP provides a blueprint for instruction and gets parents and educators on the same page. Use these simple strategies and Quick Guide for planning and writing IEP goals that support cohesive, meaningful, relevant, and effective instruction.

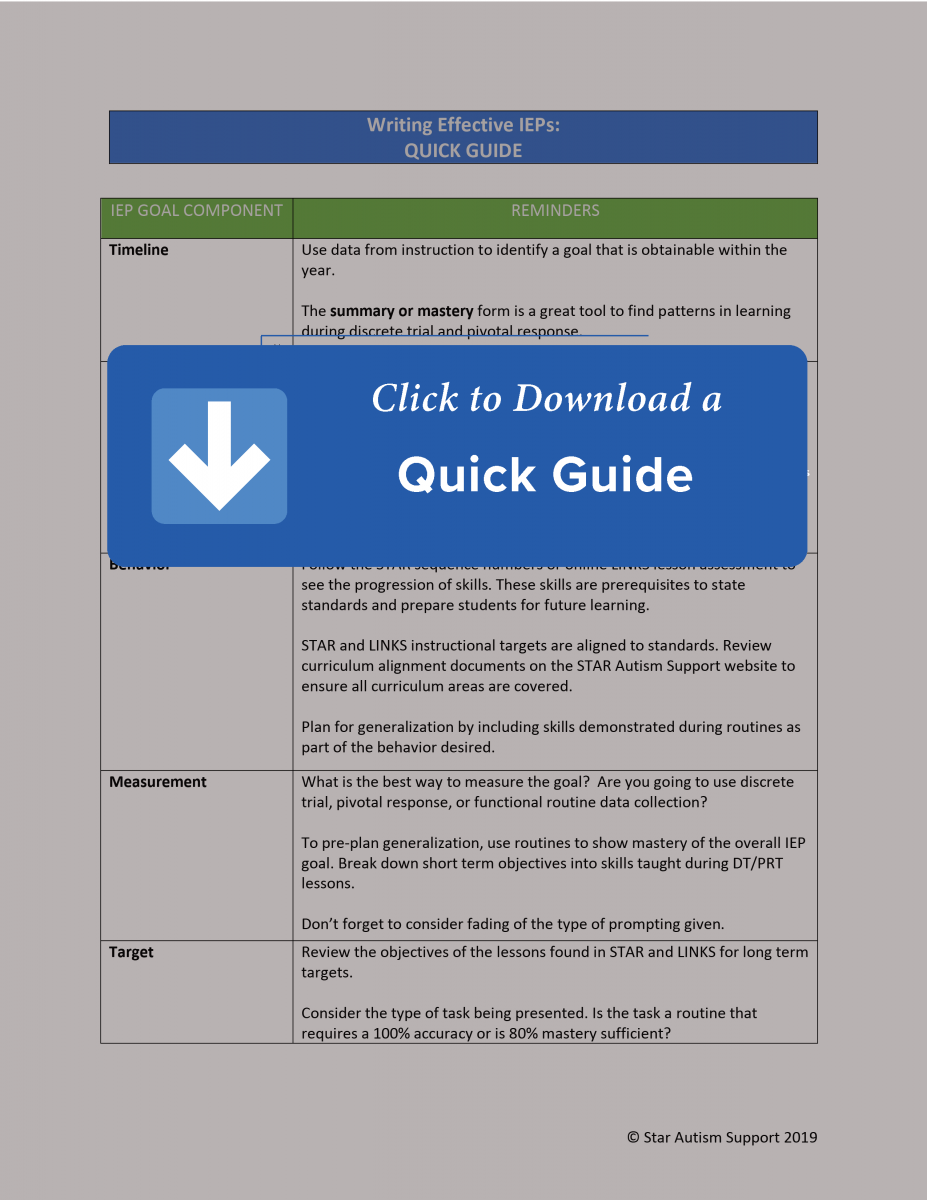

Components of a Well-Written IEP Goal

TIME

- Does a student need a year to learn the skill you are targeting? Is this skill a smaller target that can be met in an objective or benchmark instead?

- How long does it take the student to learn and maintain one new concept?

- Use the summary or mastery form from the DT data collection sheet to find patterns in learning. This will help you write a goal that is obtainable within the IEP’s timeframe.

CONDITION

- What supports student success throughout instruction? Do you have documentation of supports compared to other instructional interventions/strategies? Integrate these supports and strategies into the condition of the goal so that it is clearly communicated to anyone providing instruction.

- What is currently preventing the student from making progress? Add a condition to help the student overcome this barrier. For example, if a student has a difficult time attending, a possible condition would be, “With no more than one verbal and visual prompt to look at the teacher, the student will _________.”

- What kind of prompting are you using during routines, discrete trial, or pivotal response training? If a student is using full physical prompting, can you try to decrease that to just a visual prompt?

- Don’t forget reinforcement! Make sure you address the student’s specific reinforcement needs in the condition.

BEHAVIOR

This section is the heart of the goal! With both the STAR and LINKS programs, we focus on what we want students “to do” throughout the day. Remember these details when choosing a skill to target:

- The curriculum is a developmental scope that avoids gaps in learning. Where is the student currently functioning? Follow the STAR sequence numbers or online LINKS lesson assessment to see the progression of skills. These skills are prerequisites to state standards and prepare students for future learning.

- Don’t forget generalization. Although it’s great to master a skill in discrete trial, it’s even better to demonstrate that skill during a routine! During instruction, use activities from the Themes First! or Routine Teaching Units to seamlessly generalize skills and lead to overall success on other IEP goals.

MEASUREMENT

Measuring a student’s progress is crucial both in terms of tracking progress and documenting a potential need for adjustment:

- How do you intend to measure the goal? Are you going to use discrete trial, pivotal response, or functional routine data collection?

- Don’t forget to consider fading the type of prompting given. Decreasing the most restrictive prompting will increase student independence and provide a way to measure student progress.

TARGET

When considering the mastery criteria, review the objectives of the lessons found in STAR and LINKS:

- When does a student master the lesson and at what level is the student currently functioning?

- Consider the type of task being presented. Is the task a routine that requires a 100% accuracy? Keep in mind that the amount of mastery required varies from routine to routine. For example, asking for 80% mastery for the “Crossing the Street” routine would allow for some potentially dangerous situations. Yet, asking for 80% accuracy on the “Playing a Game” routine would be a safe and reasonable target.

Although there is no possible way to write an IEP for every element a student needs to learn, carefully planning each required component of the IEP goal can help you design cohesive instructional supports and strategies for all staff to implement. Focus on what will help a student make progress overall when deciding how many goals to write. Remember: all goals are stepping stones to the next setting. Goals should be targeted to lead to independence in general education, home, and community settings.